Outraged Over Violent Crimes, Residents March On Town Hall

/By D. Schrafel & A. Dollinger

The chant was a steady one – “Stop the crime, stop the violence, they all matter” – as hundreds marched from Heckscher Park to Huntington Town Hall one hour before the start of Tuesday evening’s town board meeting.

Community members marched for Maggie Rosales – the 18-year-old Walt Whitman High School student who was found lifeless and face-down on a Huntington Station street on Oct.12. As of press time on Oct. 22, police have given no updates and have made no arrests.

But this was about more than Maggie. This was also about Daniel Carbajal, 25, who was shot and killed outside a Huntington Station residence in July; this was about Luis Ramos-Rodriguez, 38, who was stabbed to death outside of a Huntington Station restaurant; this was about Sarah Strobel, 23, whose body was found in the woods of Froelich Farm preserve last October. Each of these is an unsolved homicide that took place over the past year.

“We need to take back our town,” said Mary Beth Steenson Kraese, who helped to organize the march. “It starts today.”

Picket signs in the hands of both adults and children read “Demand Justice” and “Definition of Apathy? Frank Petrone and the Huntington Town Board,” among other slogans and rhetorical questions.

When the marchers reached Town Hall, they crowded around a podium outside.

The Guardian Angels, led by Curtis Sliwa, vowed to come back to Huntington Station to continue the volunteer gang-and-violence-fighting efforts they started in 2010, after a rash of violent crimes led to the closing of the Jack Abrams School.

“We will never forget; we will never forgive; we will be with you, side by side,” Sliwa said.

Xavier Palacios, an attorney and Huntington school board trustee, escorted both Rosales’ and Carbajal’s fathers to the event.

“Maggie, Danny, and other young lives have been tragically lost to senseless violence on these streets and we are fearful that there is no end in sight,” Palacios said, noting that he was speaking on behalf of the Rosales and Carbajal families but also the Latino community of Huntington. “This rally is a proclamation that residents of Huntington stand together, united as a community in mourning and a community in desperate need of change. This gathering is also a declaration of frustration with how the issues of safety have been addressed in this town.”

In the Latin American community, Palacios said, many have come to Huntington in pursuit of “the American Dream.” Rosales’ parents came to the United States more than 20 years ago, he said.

“We see our futures more so as Americans than we see it as anything else,” Palacios said. “But sadly, we don’t always matter. We’ve lost our children to these streets and our losses don’t seem to matter much.”

Jessica Benitez, who said she was a close friend of Rosales’, spoke of the fear throughout the community.

“I am afraid to walk out of my house, afraid that something would happen; afraid that something would happen to those whom I care about,” she said.

Tensions Flare At Board Meeting

Following a deliberately peaceful and organized march, many of those who attended the town board meeting grew rowdy and impatient. Security guards allowed entrance to the meeting incrementally, keeping a line of attendees outside meeting room doors. Those who had signed up to speak during public portion first heard updates from Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone and Suffolk Police Chief James Burke.

Bellone’s introduction was met with boos.

“It’s a moment of opportunity to say, ‘What else can we be doing? How else can we come together?” Bellone said.

Burke’s speech, also, was interrupted by several individuals shouting out criticisms.

“It’s our job to strive to prevent crime from happening,” Burke said; but when it does happen, the police have an obligation to elected officials, to the victims’ families and – the “ultimate obligation” – to the victims themselves, he added.

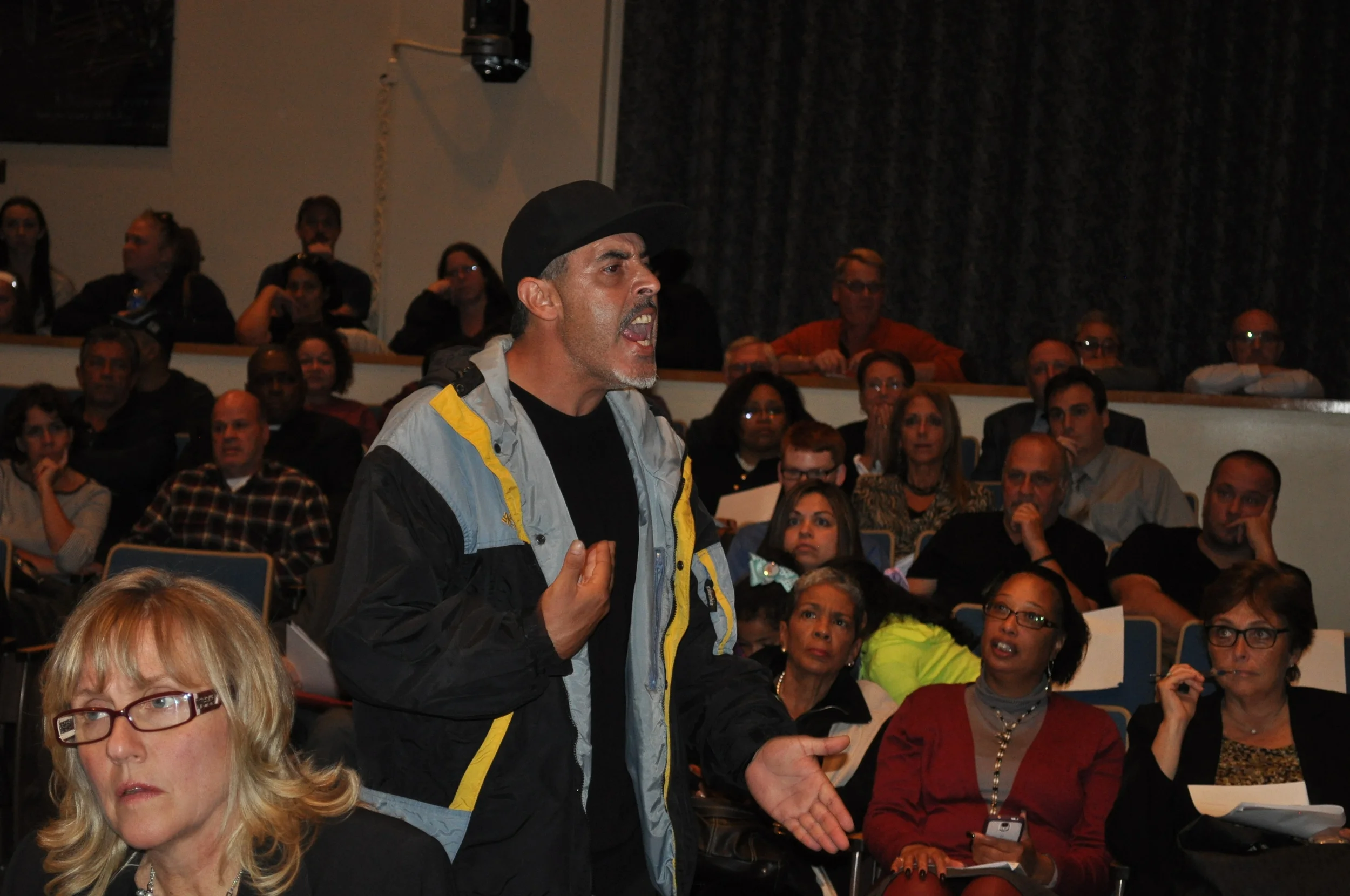

The meeting became one freckled with heckling sessions, as town board members sat calmly and informed their audience that public portion was to follow routine town board business.

When that time came, the already-bubbling anger seemed to have reached its boiling point.

“There is so much power in this room, people. So much,” said Huntington resident Aragorn Batsford, waving in the air the papers on which he had been taking notes throughout the meeting. “I can’t even express how disappointed I am.”

Huntington Station resident Jim McGoldrick said that he lives across the street from the spot on Lynch Street where Rosales’ body was found. According to McGoldrick, police arrived at 11:30 p.m. but the investigative team did not arrive until almost six hours later.

“I asked the detective why they haven’t covered or blocked the body of Maggie from our community after eight hours,” McGoldrick said, to gasps from his audience. “I was told it would contaminate the crime scene.”

McGoldrick, who met privately with Councilman Eugene Cook, Supervisor Frank Petrone and the town’s public information officer, A.J. Carter, publicly resolved to be at every town meeting from now on.

“I will make sure Maggie gets her justice,” McGoldrick said.

Kraese, who had addressed the crowd after the march, took to the podium to ask the town: “Tell us: What are you going to do differently now?”

“Our children are now afraid to go to school,” Kraese said. “And their parents are afraid to send them.”

Seth Cannon, Rosales’ pastor at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Huntington Station and a resident of East Northport, said that some members of his congregation are now afraid to travel to church at night.

“The members of our congregation do not feel safe [since Maggie passed away],” he said.

A group of girls who said they were close friends of Rosales stood behind the microphone several times during the meeting, as a group.

“Seeing that empty seat in front of us and in lunch just breaks my heart,” said Jackie Benitez. “We are teenagers, just like Maggie was, and it could’ve been one of us.

Several who were on the list of speakers during public portion decided not to discuss their respective issues after seeing the community’s outrage about Maggie, deciding that their issues seemed trivial now.

After leaving the meeting room, Maggie’s father, Cesar Rosales, said that he thinks the number of people who attended his daughter’s funeral and the night’s events was a result of an epiphany in the community. The community has arrived at this moment in which they are recognizing that there are people dying on the streets, he said.

Before his daughter’s death, Rosales said, he was not concerned about the area in which his family lives.

“On these streets, previously, I hadn’t [heard about] problems. The problems I’d heard about were on the side of the train station, 11th Street, the [Jack Abrams school],” he said, in mixed Spanish and English.

Mourning Maggie

At A.L. Jacobsen Funeral Home Oct. 17 where hundreds gathered to pay their final respects to slain Walt Whitman High School senior Maggie Rosales, several speakers, reflecting on the 18-year-old’s joyous zeal for life, told mourners she would want them to be strong, that she wouldn’t want to see her friends and family members in pain.

But the guttural sobs that pierced the silence of the intimate funeral chapel that grew more crowded as the service continued reflected the immeasurable sorrow of the senseless, violent death of a young woman found stabbed to death on Lynch Street off of Depot Road in Huntington Station Oct. 12.

Flowers and photo collages of images chronicling Rosales’ life lined the chapel, where she lay in repose in an open casket, dressed in white. “We love you Maggie – forever in our hearts,” one read.

“She was a light amidst the darkness we sometimes face on Earth,” said Janet Srinivasan, a youth leader who worked closely with Rosales in recent years.

She was known by friends for her kindness and the unconditional love she shared with others, Srinivasan said, adding that the most profound way to pay tribute to her memory was not to dwell on the way she died, which would give “more power and fame to evil,” but to “remember the person she was and be more like her.”

Bishop Seth M. Cannon, pastor of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Huntington Station, said Maggie brought hope for “more peace in our world and our community and hope for a better tomorrow.” Her middle name, “Esperanza,” is Spanish for hope, and Maggie’s birth gave her mother, Ignasia, great hope at a difficult time in her life, Cannon said.

“Maggie taught us that we must give love,” he said.

Friends and family tearfully remembered Rosales’ loving nature, nights watching scary movies, sharing meals and going to parties with her.

Douglas Arevalo, Maggie Rosales’ boyfriend, was a pall bearer at his girlfriend’s funeral.

“Thank you for all the years you gave me,” he said to Rosales, trembling as he spoke. He could say little more before hugging Ignasia Rosales, sobbing.

A march in Maggie’s honor before the Oct. 21 Huntington Town Board meeting was well-attended by family members and Walt Whitman High School students.

Pablo Jimenez, one of Maggie’s cousins, said in Spanish that she was “amable, alegre, contenta, feliz” – nice, happy, content, just happy.

Erika Hoffman, who graduated Walt Whitman High School last year, said that she remembered Rosales.

“Anyone that really needed a friend, or didn’t have friends, she would kind of take in,” Hoffman said. “That’s what I remember about her.”

Walt Whitman High School senior Jackie Hoffman, who said she was in classes with Rosales, said that she attended the march because “the town’s not doing enough.”

“She was just really, really sweet,” Hoffman said of Rosales. “She cared about everyone… She was just nice to everyone she met.”

At the conclusion of the march, Jessica Benitz said that Rosales was “unique.”

“She was a unique young lady, who cared about others, who gave a hand to who needed it,” said Jessica Benitez. “Maggie’s journey was just beginning.”

Maggie Rosales’ father, Cesar Rosales, said that his daughter was one who enjoyed the social activities all of the young people enjoy.

“She was a girl who liked, like all young people,” he said in Spanish, “to go to a party, to go out with her friends.”

She had a boyfriend and friends and would come and go as she pleased, he said, whenever her friends called her.

Cesar Rosales said he does not know exactly where his daughter went the night she was killed; as far as he knows, she was going to meet a friend and thought that they were going to a party. Because of the nature of the investigation, he said he could not say anything further.