Taking To The Sky, 1940s Style

/I’m in a two-man, open-cockpit plane, wearing a helmet and a jumpsuit. There is a parachute strapped to my back. I have just been informed that we will not be high enough for said parachute to do me any good.

And what am I worried about? Working the video camera strapped to the cockpit.

“I figured out how to use the GoPro,” I say. There’s an intercom built into my helmet, but I still have to shout over the noise of the engine.

“You’ve got one up on me!” pilot Bob Johansen says.

For a second, I’m unsettled. One up on him? We’re waiting on a very windy Republic Airport runway. Shouldn’t the pilot know more about—I don’t know—everything than I do?

I remind myself that Johansen, who spends his summers in Northport, doesn’t need to be up on the latest technology; he’s flying a World War II training plane for the GEICO Skytypers. That technology is from 1940. I also remind myself that aviation and point-and-shoot video cameras have little in common.

The Skytypers team consists of a dozen pilots. They do air shows across the country, from New York to Virginia to Georgia, but Long Island is their home. They’re also in the business of “typing” messages in the sky using puffs of smoke.

The team, owned by Northport resident Larry Arken, is a common draw at the New York Air Show at Jones Beach each Memorial Day Weekend. Arken also serves as the commanding officer and flight lead. Flight is in his blood; he inherited the team from his father, the late Mort Arken.

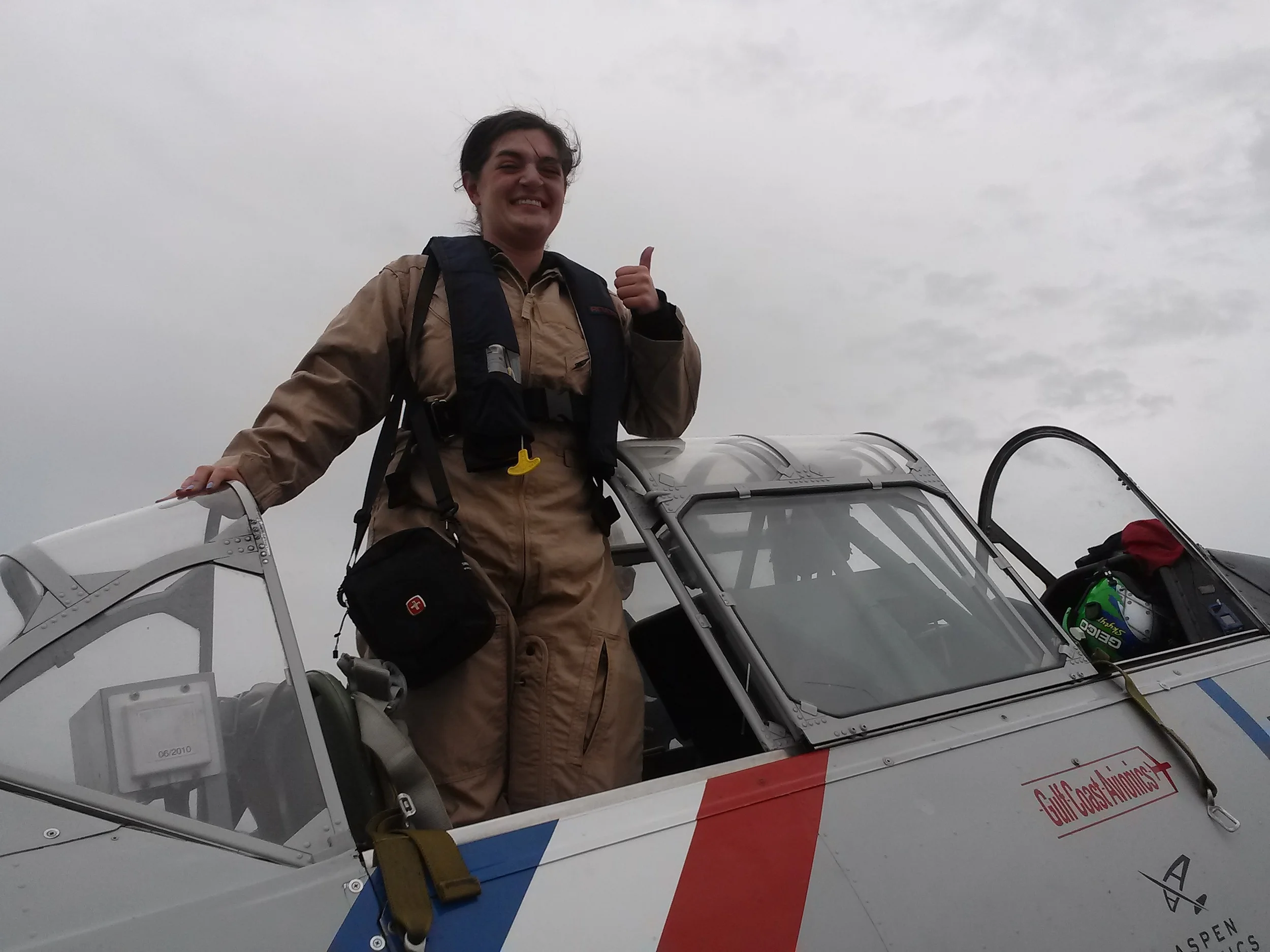

I’ve seen the itty-bitty propeller planes before; I never thought I’d be in one. I’m on a rare media-flight with the Skytypers. The crew has graciously allowed me to see what they do up close. In exchange, I’m playing the part of “fearless reporter.” So far the scariest part has been climbing into the plane, which involved bracing my foot on a tiny metal foothold that I could barely reach with my toes. I am now in the plane. So far, I think I’m doing a decent job.

Johansen’s been flying since he was just 17 and joined the Skytypers in 1977. In between, he flew the Grumman S2 “Tracker,” an antisubmarine aircraft from aircraft carriers. He also spent 33 years working as a commercial pilot—I don’t think I would need my useless parachute even if it were useful.

We’re still on the runway, getting ready to take off beside Jim Record, another pilot for the Skytypers. Flying with multiple planes will give me a rare glimpse of flying in a close-flight formation. The group does close formation stunts. I’m told they even go wing to wing.

I realize that my helmet-intercom picks up words from ground control. I listen to the scratching sounds with impatience. I’m done taxiing; I’m ready to fly. I start thinking I should be more nervous than I am. I stop thinking.

The cockpit canopy is open. We have liftoff. The flight is so smooth that I barely realize that we have liftoff.

Once we’re in the air, I can see Record give us a thumbs-up. He’s flying just ahead of us. I don’t think he can see me. I don’t think the thumbs up was intended for me. I flash one back, anyway.

“I bet you never thought you’d be this close to another plane before,” Johansen says.

His bet is accurate—never in my wildest dreams had I thought this would be possible. I can’t stop laughing.

“Normally, if you’re flying and you see another plane, it’s not a good thing; but [with us] it’s actually easier when you’re closer, because the whole game is relative motion. The closer you are the easier it is to see what he’s doing,” he continues.

I continue giggling like an idiot in response. I can barely hear him over the wind and engine. My ears feel like they need to pop.

The beach looks tiny from 1,000 feet. The plane beside us does not look so tiny. In fact, it looks larger than it did on the ground. It’s amazing what happens when your point of reference shifts.

I can’t get over the fact that a propeller is what pulled us into the air. We’re over open water. I can’t stop looking at the other plane. I can’t stop thinking about what we must look like from the other plane. It’s like being inside of a toy.

The cockpit is roomier than I had expected. There is more space in front of my body. With the air around my face, I feel like I’m sitting in a solitary chair in the sky. It’s noisy.

I feel compelled to gush to the pilot.

“This is incredible!” I say.

“This is our life!” he says.

Each time we turn, the plane flips sideways. This is my favorite part, by far.

Suddenly, there’s smoke around us; I look at our companion plane and realize that we’re making a “dash” in the sky. I remember that they’re called “Skytypers” for a reason.

We circle back and see our own mark hanging in the sky. Up close it looks like some strange, angular cloud.

The planes they fly—SNJs—were designed to help pilots transition between basic trainers and first-line tactical aircrafts in 1940-1941. Most Allied pilots who flew in WWII learned in an aircraft just like the one I’m sitting in.

I think about the history of the planes, about flying one in times of war. It seems sort of lonely, just you and the pilot in the sky. I look over at Record in plane #6. Not so lonely anymore.

Ground control scratches back into the intercom.

“It’s gonna be a hard turn, either left or right,” a voice says.

“Copy that.”

We take a left.

After a little more cruising, the announcement comes—gear down now. My heart sinks a little; I don’t want my ride to end!

The landing is smooth. I tell Johansen how awesome his life is. I try to turn off the GoPro. I later learn that I failed to turn off the GoPro. I take a deep breath. Just as I finish exhaling, the intercom clicks off. The adventure is over.